You can find all the details about the original research study here

In January 2020, the founder of this citizen science project, Monty Lord, completed the original clinical research study that this project is based upon. You can find all the research findings from that original study and download a copy of the original report on this page.

Click the button below

Monty's original research study ran to several hundred pages and with a word count of approximately 55,000 words, has been described by one university professor as sitting between a Masters & a PhD thesis.

To read all of the original findings & statistically significant correlations, along with suggestions for prevention & intervention strategies, just click on the button below to download the report in pdf format.

In the original study, 864 adolescents, aged between 11 and 17 years old, from 3 academic establishments in the UK took part. The main independent variables in the study were type and frequency of electronic devices used at bedtime, hours of sleep during both weekdays and weekends, sleep quality and daytime attentiveness.

Members of the teaching faculty at the partaking academic institutions distributed a two-page questionnaire by hand to all students present in their classes. These faculty members informed their students that participation was both anonymous and voluntary. Students were given the questionnaire to complete during either a form registration period or class time in order to expedite collection of the data samples and to maintain a relatively quiet and controlled environment in which the questionnaires can be completed.

Research Findings

The research findings were broken down into the 3 core areas of sleep, bedtime technology and circadian rhythms, followed by some general analysis and the use of SPSS statistics software to identify statistically significant correlations. Some of the key findings are below.

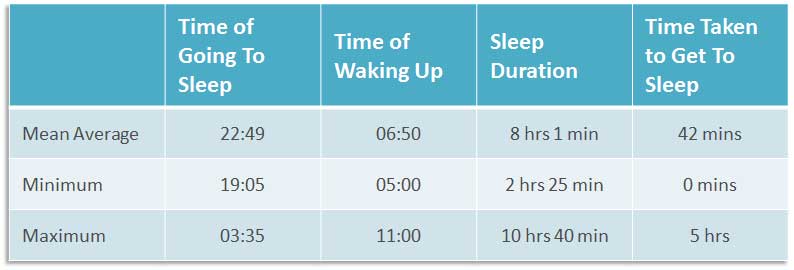

Sleep Pattern

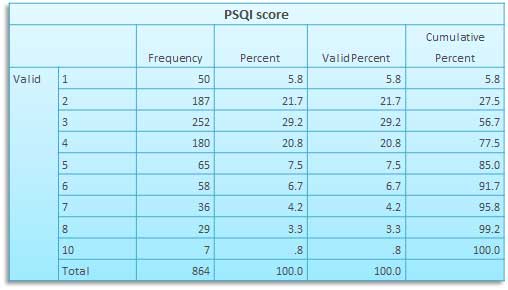

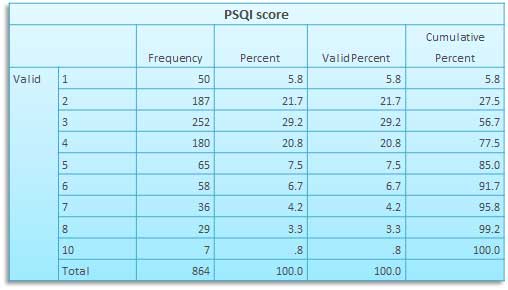

Sleep Quality

Respondents were asked how they rated their overall sleep quality over the previous month:

- 7.5% (n= 65) rated their sleep quality as very bad

- 25.8% (n= 223) rated their sleep quality as fairly bad

- 55% (n= 475) rated their sleep quality as fairly good

- 11.7% (n= 101) rated their sleep quality as very good

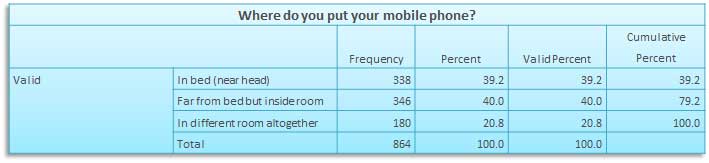

Sleep Environment

Technology

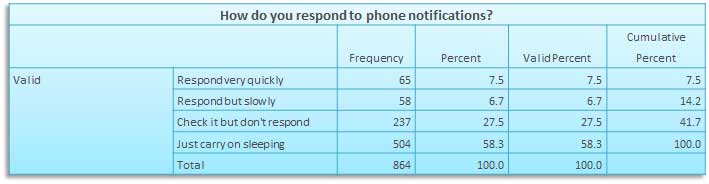

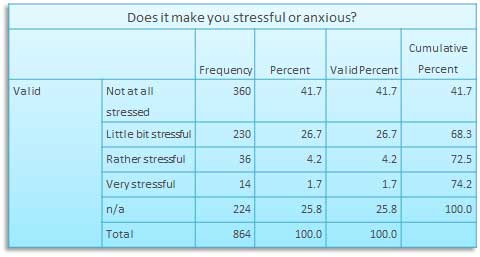

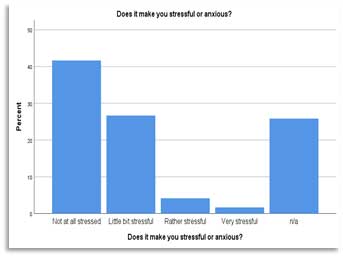

32.6% viewed accessibility via mobile phones to be stressful and made them feel anxious.

Most adolescents delay their bedtime due to some form of technology (78.5%, n= 684).

Circadian Rhythms

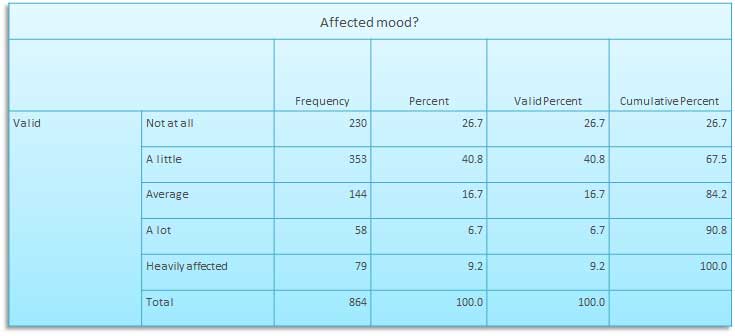

73.3% of the respondents stated that they felt their quality of sleep has affected their mood, energy levels or relationships.

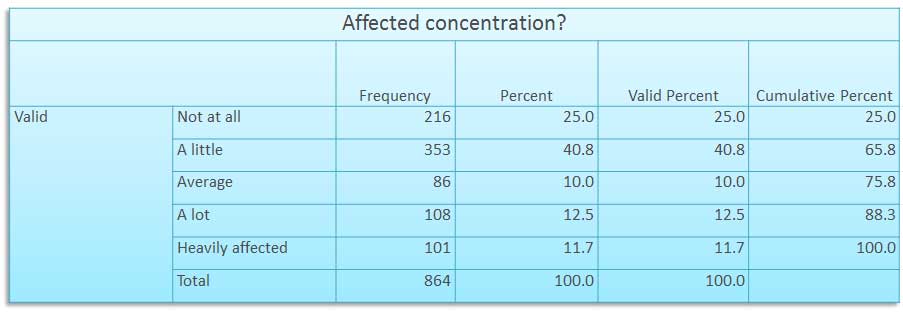

75% of the respondents stated that they felt their concentration, productivity or ability to stay awake has been affected by their quality of sleep.

From this data set we can see that there is a statistically significant relationship between adolescents who go to bed later at night and their awaking the following day, feeling irritable or angry. This indicates a link between later bedtimes and circadian rhythms. We would have to therefore address the reasons behind these later bedtimes.

There are 3 correlations of extremely high statistical significance in the relationship between adolescents who have reduced sleep duration and their awaking the following day, feeling irritable or angry; or awaking from sleep with drowsiness or feeling unrefreshed during the daytime at school; or having trouble staying awake in school, eating meals or engaging in social activity. This also suggests a link between sleep and circadian rhythms.

There are also 2 correlations of extremely high statistical significance in the relationship between adolescents who have rated their sleep quality poorly and their awaking the following day, feeling irritable or angry; or awaking from sleep with drowsiness or feeling unrefreshed during the daytime at school. Another link between sleep and circadian rhythms!

There is a statistically significant relationship between adolescents who delay their bedtime due to using some form of bedtime technology and an increase in their delayed bedtime (Sleep Onset Latency). This answers our question as to why adolescents may have later bedtimes, due to the use of bedtime technology. This is supported by the further correlation of extremely high statistical significance in the relationship between whether adolescents felt they could improve their own sleep quality and the feeling that bedtime technology has affected their sleep.

The results also show us 3 correlations of statistically high significance in the relationship between whether adolescents felt they could improve their own sleep quality and those who felt that their quality of sleep affected their mood, energy levels or relationships; or those awaking from sleep feeling irritable or angry; or the frequency with which they felt drowsy or unrefreshed during the daytime.

There are 2 correlations of extremely high statistical significance in the relationship between adolescents who experienced an increased frequency of troubled sleep because they had been awoken by phone notifications and those who felt they usually awake from sleep still feeling irritable or angry; or those who reported an increased frequency of feeling drowsy or unrefreshed during the daytime. This shows an affected circadian rhythm and is a natural assumption that punctuated sleep leads to an affected mood the following day.

The data set also provides us with 2 correlations of statistically high significance in the relationship between adolescents who experienced an increased frequency of troubled sleep because they had been awoken by phone notifications and those who felt a reduction in the quality of sleep was affected their mood, energy levels or relationships; or those who experienced trouble staying awake in school, eating meals, or engaging in social activity. Again, this is indicative of troubled sleep which is directly affected by a form of bedtime technology, mobile phones. This also shows a connection between bedtime technology, affected sleep and affected circadian rhythms.

There is 1 correlation of very high statistical significance in the relationship between the frequency that adolescents delay their bedtime due to bedtime technology use and those who awoke from sleep feeling tired or sluggish, providing another link between bedtime technology, sleep and circadian rhythms.

There is also a correlation of statistical significance in the relationship between whether respondents felt that bedtime technology affected their sleep and how often they felt drowsy or unrefreshed during the daytime, showing another causal link.

There is a correlation of statistically high significance between adolescents who felt anxious when separated from their bedtime technology and the total PSQI score of the adolescents. PSQI is a measure of sleep quality.

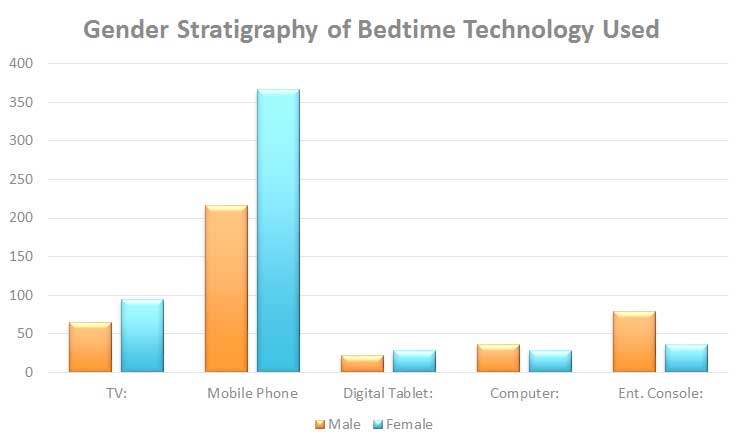

The majority of adolescents in this study reported delaying their bedtime due to some form of bedtime technology. It’s clear that the majority of adolescents felt that mobile phones were the form of bedtime technology that was most associated with stopping them getting the ideal amount of sleep. This is most likely due to their multi-functional nature, combining many different forms of entertainment in one compact and portable unit. The television was the next form of bedtime technology that stopped adolescents from getting their ideal amount of sleep.

There are 2 correlations of statistical significance in the relationship between the Diurnal Type Scale (DTS) and where they put their mobile phone during bedtime; or the frequency that adolescents delay their bedtime due to the use of bedtime technology. It also shows a correlation of very high statistical significance in the relationship between the Diurnal Type Scale (DTS) and those adolescents who went to bed at a later time. These results in themselves are suggestive of a causal link between bedtime technology use on reduced or disturbed sleep and the resulting affected circadian rhythms, typifying adolescents as either morning or evening-typed.

The majority of adolescents in this study, reported that they could sleep for longer. This indicates a very high tendency towards an accumulation of sleep debt over the week. The majority also stated that they felt they could improve their quality of sleep.

The majority had been awoken during their sleep by bedtime technology and just under half of the adolescents said that they felt that electronic devices affected their sleep. The majority also stated that their quality of sleep had affected their mood, energy levels, relationships, their concentration, productivity or ability to stay awake and that they had trouble getting to sleep.

The Conclusions

This study focused on adolescents with my hypothesis being that using bedtime technology at night adversely affects their circadian rhythm. The research shows that adolescents who use bedtime technology, especially mobile phones, late into the night, has consequences on overall sleep quality.

Hypothesis Proven!

We’ve been able to demonstrate that the use of bedtime technology results in a reduction in sleep duration, altered sleep patterns, increased frequency of sleep disturbances and delayed sleep onset.

This research study has also shown that there is a strong relationship between the use of bedtime technology, daytime inattention and somnolence. Along with this, the results show a causal link between the use of bedtime technology and an increase in daytime drowsiness, irritability, anxiety and lethargy.

The theory and previous research studies indicate that sleep is negatively affected by both blue light emissions from bedtime technology with screens and the psychophysiological arousal from viewed content. Whilst this research study has been unable to scientifically prove this, it has been able to demonstrate a significant relationship between bedtime technology with screens and affected sleep and circadian rhythms.

Based on the empirical evidence in this study, I find that there is a definite and significant relationship between the late night use of bedtime technology and the many effects it results in on the circadian rhythms of adolescents. On that basis, my hypothesis is proven.

The next step is to find ways to deal with this and better educate both adolescents and parents about not only the harmful affects of bedtime technology but also the potentially harmful effects of completely removing bedtime technology from adolescents with an unmeasured approach. The overall scope of this research study suggests that there is a public health issue arising here and that intervention and prevention strategies are required. Intervention strategies should always seek to involve parents, the education system, the health service ….and of course, the adolescents themselves.